Crafting a Masterpiece

Saturday, September 20, 1997

By Marlene Monfiletto, Eagles Times Correspondent

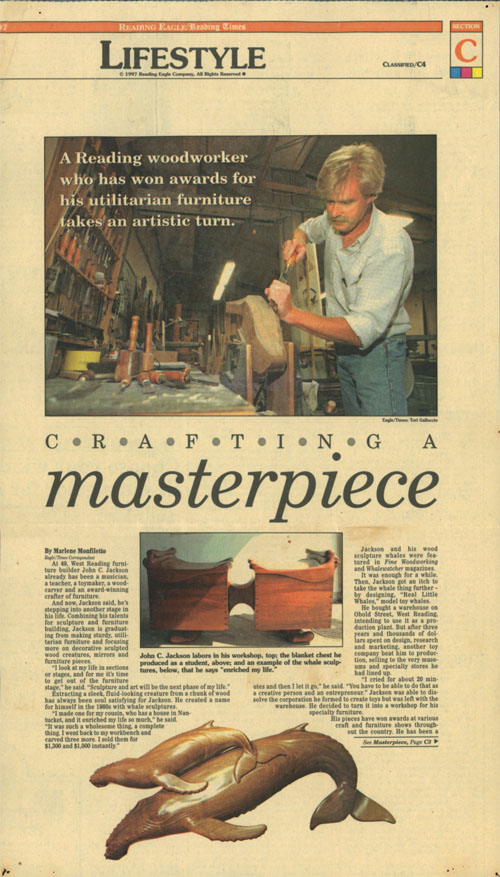

Caption from photo: John C. Jackson labors in his workshop, top: the blanket chest he produced as a student, above; and an example of the whale sculptures, below, that he says “enriched my life.”

A Reading woodworker who has won awards for his utilitarian furniture takes an artistic turn.

At 49, West Reading furniture builder John C. Jackson already has been a musician, a teacher, a toymaker, a wood-carver and an award-winning crafter of furniture.

And now, Jackson said, he’s stepping into another stage in his life. Combining his talents for sculpture and furniture building, Jackson is graduating from making sturdy, utilitarian furniture and focusing more on decorative sculpted wood creatures, mirrors and furniture pieces.

“I look at my life in sections or stages, and for me it’s time to get out of the furniture stage,” he said. “Sculpture and art will be the next phase of my life.”

Extracting a sleek, fluid-looking creature from a chunk of wood has always been soul satisfying for Jackson. He created a name for himself in the 1980s with whale sculptures.

“I made one for my cousin, who has a house in Nantucket, and it enriched my life so much,” he said. “It was such a wholesome thing, a complete thing. I went back to my workbench and carved three more. I sold them for $1,300 and $1,000 instantly.”

Jackson and his wood sculpture whales were featured in Fine Woodworking and Whalewatcher magazines.

It was enough for a while. Then, Jackson got an itch to take the whale thing further -by designing, “Real Little Whales.” model toy whales. He bought a warehouse on Obold Street, West Reading, intending to use it as a production plant. But after three years and thousands of dollars spent on design, research and marketing, another toy company beat him to production, selling to the very museums and specialty stores he had lined up.

“I cried for about 20 minutes and then I let it go,” he said. “You have to be able to do that as a creative person and an entrepreneur.” Jackson was able to dissolve the corporation he formed to create toys but was left with the warehouse. He decided to turn it into a workshop for his specialty furniture.

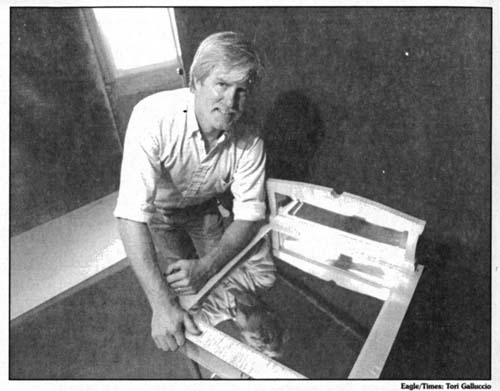

John Jackson of Jackson Woodworks stands by a wet bar he designed and made

His pieces have won awards at various craft and furniture shows throughout the country. He has been a regular at the Philadelphia Furniture Show, held each year in May. He has a handful of dis¬criminating furniture buyers who collect his signed work and a portfolio documenting where each piece has gone. The names of his collectors are kept private.

In his office/showroom he has a few of his favorite designs – a three-legged table and stool set, a utilitarian-looking table and ben¬ches, two hippopotamus blanket chests and a copper-topped dry bar. A master woodworker, he has been commissioned to build top-of-the-line cabinetry in prestigious homes.

One of his favorite pieces is on display in a dean’s office in Georgetown University, Washing¬ton, D.C. The glossy dry bar is made from curly maple and finished with subtle curves, a copper top and hardware. The commissioned piece took 350 hours of work to complete.

“My furniture is the simplest design you can get but that will last,” he said. “They’re designed in such a way that they’re durable from one generation to the next. I guarantee my furniture will last 300 years, or I will come and fix it personally.”

Jackson said the durability of his furniture is the result of his production process – the same one woodworkers used 100 years ago. There are no screws or metal fasteners holding together the joints of his pieces. Instead, Jackson cuts mortars and tendons into the joints which fit together like a puzzle. He secures them with wood fasteners.

Although Jackson describes some of his contemporary furniture as working class style, he admits the cost of each piece is probably out of reach for most of the working class. The dry bar costs about $5,600 and the table, about $2,700.

“My standards are as high as the material and work will allow,” he said. “I feel a responsibility to make things to stand the test of time. This is what I learned when I went to school. To be a real credible craftsman artist, you have to achieve the highest quality you can.”

Jackson’s first taste of woodworking came in a high school shop class. Later, he attended the Philadelphia School of Art, majoring in ceramics and crafts. Eventually he picked up on the art of furniture making and wood sculpting there, too.

But his heart was pulled in another direction. A long-time guitar and bass player. Jackson took off two years to join a band and pursue a musical career. He was one of the original members of Johnny’s Dance Band, one of the premier Philadelphia bar bands in the 1970s.

He also played in bars at the Jersey shore, Harrisburg and in Newark, Del. Later, his band was the opening act for Bonnie Raitt and Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes.

After a few years. Jackson and another band member took off for Los Angeles, attempting to be¬come staff songwriters for some of the big record companies. That dream never came to be.

“I realized I had gone as far as I could go with the music,” he recalled, “and boom! The next day I was back doing woodworking and sculptures.” He also taught at the Philadelphia College of Art, Drex-el University and Bucks County Community College and was restoring an old mill in Pottstown. It was during that time he met his wife, Janet, and moved to Berks

County. They have three children.

Jackson kept in touch with band members and still plays with three of them in the Big Rhythm Band, in regional clubs and events.

“It’s good for the soul,” Jackson said. “I continue with music for that reason.”

Jackson puts his soul into each piece he creates, too. But with the furniture business becoming saturated with creative and competent craftsmen, Jackson feels it’s time to take another turn – a return to his wooden sculptures and sculptured furniture.

“In the 1970s, I could list on both hands and feet the quality furniture craftsmen,” he said. “Today there are more than 1,000 like myself who do this work. It’s very competitive for one-man shops, and this work is intense.”